[toc]

Introduction

State-tracking firewall devices are commonly deployed at the border of data centers, office networks, and other corporate environments where precious IP needs to be kept out of the hands of others. My opinion of these firewall devices is that they should be avoided at all costs, and I’ll get into that later. Sometimes we’re forced to deploy things we don’t agree with because someone doesn’t wish to take on any risk, or doesn’t know any better. Or both. This applies heavily to firewalls, and can often lead to a very compromised network design. I don’t mean compromised as in security, but rather in scalability and flexibility.

This document will explain some different ways to deploy firewalls in a more flexible manner. Later, it’ll touch upon why firewalls should be avoided whenever possible.

And unlike most of the rest of the documents on this blog, I won’t be including specific configuration snippets or examples. And it’s going to be a bit shorter than my other techie write-ups here. This is all high-level, 50000-foot view stuff. Let’s get into it.

Definition

Let’s first define what I mean by the term firewall. Any state-tracking security device who’s primary role is to block all network traffic unless it’s specifically allowed. These are devices that are, for instance, sold by companies like Checkpoint, or Palo Alto. The Juniper SRX, and former Netscreens are also examples. What I specifically don’t mean are routers with ACLs applied.

Firewalls: A L3 Hop

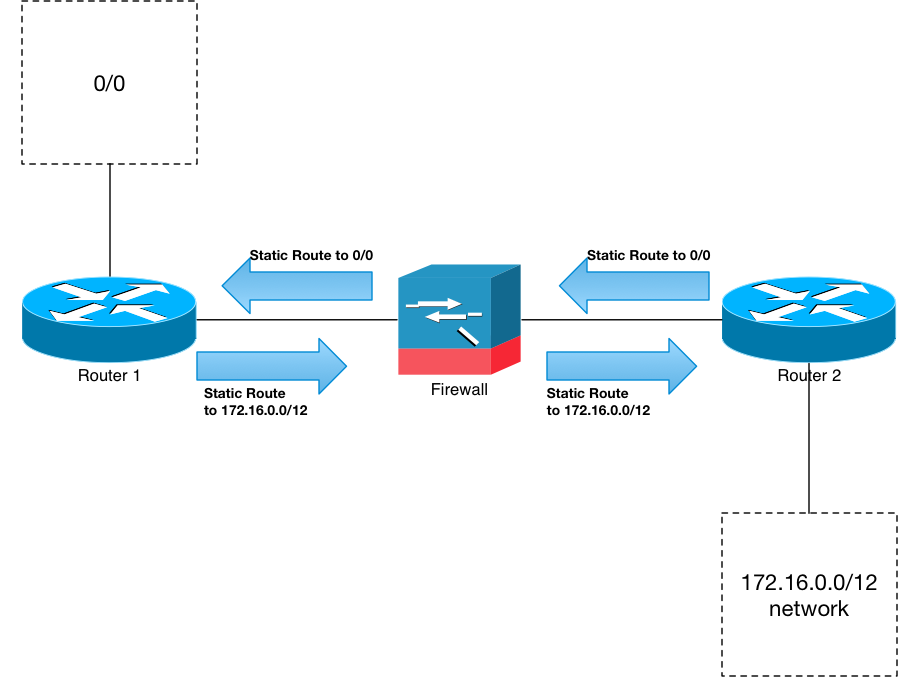

The network model I’ll use for the rest of this document is shown in the diagram above. It’s really simple, but the concepts will apply to networks that have more devices. I have two routers talking to each other through a firewall of some sort. The make and model of the firewall, and of the routers is completely immaterial.

By default, I’d have to set up a bunch of static routes in this network. If I have Router 1 being the ingress/egress of the entire network, that means it needs to act as the default route of both the firewall and Router 2. And if, say, I had a large 172.16.0.0/12 network hanging off Router 2, then Router 1 and the firewall would both need statics for that prefix. The diagram below shows that:

Router 1 either has a static 0/0 pointing out, or it’s receiving the appropriate route or routes from an external peer. But, it also has a static for the 172.16.0.0/12 prefix pointed towards the firewall’s interface. The firewall has a static default route pointed back towards Router 1, and another static for 172.16.0.0/12 pointed towards Router 2. And finally: Router 2 has its static 0/0 pointed towards the firewall.

What’s The Problem?

The above network setup is, by its nature: very static. As long as nothing in my network ever changes, I could conceivably leave the routing like that and be done with it. The only changes I’d need to make would be to the security filters on the firewall as new services are brought online and old ones are taken down. But what happens if I decide to spin up network 10.0.0.0/8 behind Router 2? Or, perhaps 10.0.0.0/8 is learned on Router 2 via another router? Well, I’ll need to go back to Router 1 and the firewall and add another static route to each.

This isn’t very flexible at all. It means that with every new prefix I have on or through Router 2, I have to add statics to both Router 1 and the firewall. And then I have to adjust the security posture of the firewall.

That’s a lot of configuration, and it’s simply not necessary.

STOP DOING IT!

Dynamic Routing: Use It

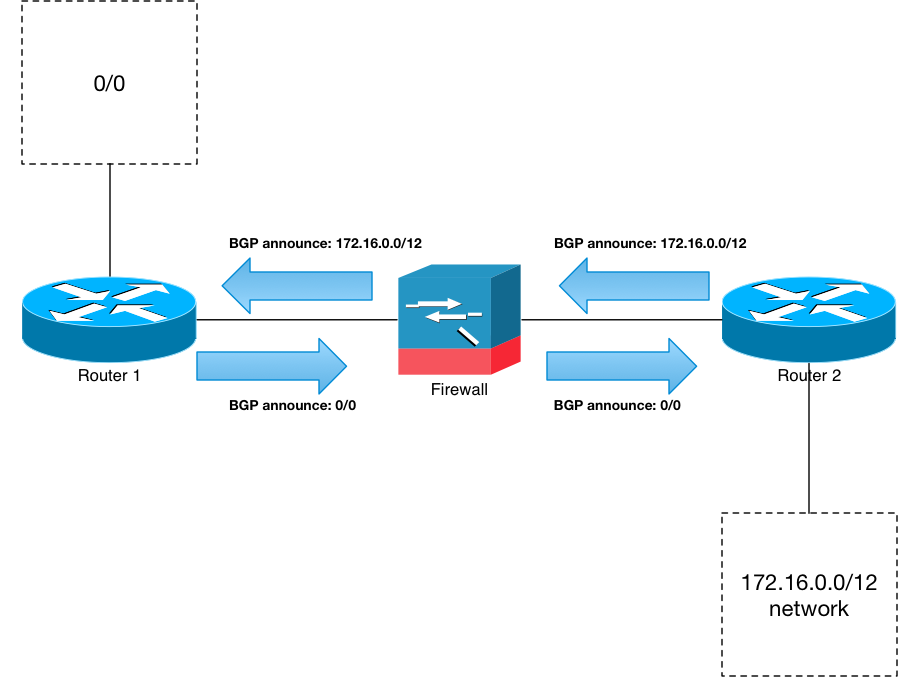

Option 1: Routing With The Firewall

Most modern firewalls support routing via BGP. We’re all network engineers, aren’t we? That means we can spell BGP. So: let’s use it! The network will look very similar to the previous one, but with an important change:

Router 1 has a BGP peer with the firewall. Router 2 has a BGP peer with the firewall. Router 1 announces its 0/0 in BGP to the firewall; that 0/0 then gets re-announced to Router 2. Likewise: Router 2 announces its 172.16.0.0/12 prefix to the firewall; which then re-announces it to Router 1.

No statics anywhere. And if a new network is built off of Router 2, it can simply be put into BGP and announced up to Router 1 by way of the firewall. The only configuration I’d need to at that point is the security posture on the firewall for the new prefix. I don’t have to worry about the routing; it just happens for me.

BGP Multihop

I could conceivably setup a BGP multihop between Router 1 and Router 2, bypassing the BGP configuration on the firewall. The problem with this is that the L3 hop in the middle (the firewall) still needs to know the destinations of the packets flowing through it. So even if Router 1 and 2 are passing BGP messages to each other via the firewall, the firewall still needs to know which direction 0/0 is, and which direction 172.16.0.0/12 is. Otherwise, the packets will get black-holed.

It’s for this reason that I’d prefer to set up an EBGP peer. I’d cook up a private ASN for the firewall, and another for Router 2.

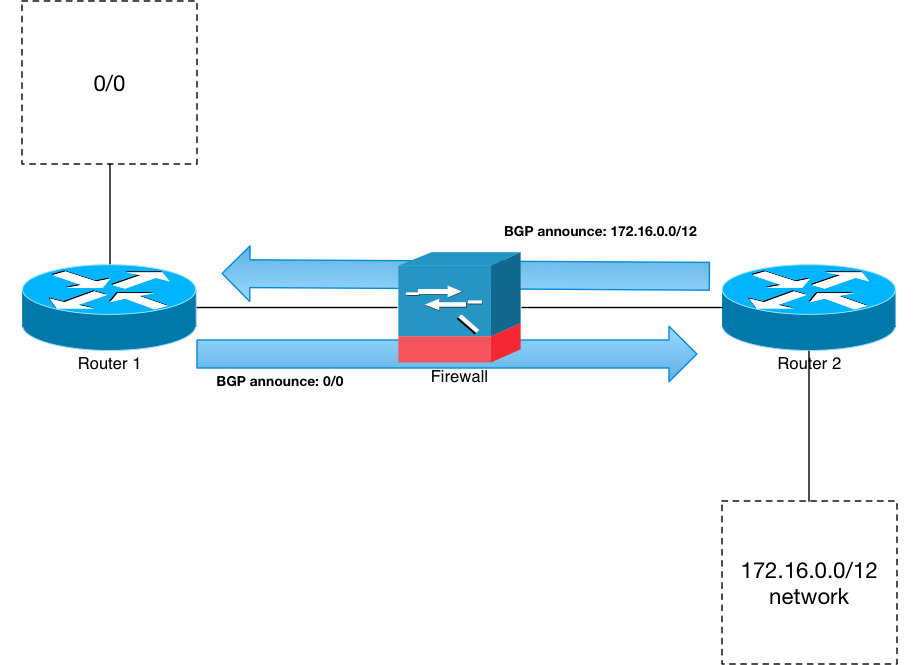

Option 2: Routing Through The Firewall

There’s another option that’s even slicker than routing with the firewall, and that’s routing through the firewall. Most of today’s firewalls support a L2 pass-through mode. In other words: the firewall becomes a bridge. It still examines every packet traversing it, but it doesn’t act as a L3 hop at all:

What I have here is Router 1 and 2 BGP-peered directly together. The firewall’s interface aren’t given an IP address at all. The interfaces on Router 1 and 2 are on the same /31 (or /30, or whatever) and they can establish BGP that way. A traceroute will show Router 1, then Router 2. The firewall will never appear. If the traffic is allowed through, it’ll go through. If not, it’ll get blocked after it egresses one of the routers, as it’s supposed to be.

Which Option?

The question of “which option should I pick?” should be the next one. Either one is dramatically better than static routing. But: it depends on the requirements. Bear in mind that I’m completely skipping the “comfort” factor of routing with or through the firewalls and focusing on the technical aspects. In other words: if you’re not comfortable with this idea, you need to get over it. I’ve moved past that point.

Sometimes you’ll need the firewall to be a L3 hop in the path. I truly believe NATting is another abomination that needs to go away. That’s a paper for another day. But: if your firewall has to act as an address translator, then it has to be a L3 hop. There’s no choice. In bridging mode, it can’t route packets. Which means it can’t NAT for them, either. So in this case, you’ll want to route with the firewall, not through it.

If you’ve set up a redundant pair of firewalls, and then a redundant pair of routers on either side of them, then care will need to be taken with routing through. The firewall pair will need a way to keep state updated between the two devices. If routing is set up with equal cost multi-pathing between the two router pairs, there’s a chance for asymmetry: the SYN traverses Firewall 1, and the SYN-ACK comes back through Firewall 2. If that happens faster than the state sync can, then Firewall 2 will drop the SYN-ACK and the 3-way will never complete. This is a case where routing with versus through may also be a good idea. Or, you can set up BGP prepends on the router pairs to force the firewalls into a fake Active/Standby configuration.

Nuke Firewalls From Orbit

If you can’t tell: I’m not a fan of firewalls. At. All. They’re an absolute abomination that need to stop being purchased and deployed. Let me talk about the “Why” before I address the “Instead” part.

The “why” is pretty simple: they screw up the network. Badly. They make efficient network architecture nearly impossible because of ECMP and state-sync’ing issues. And because of their very nature, every packet (versus every flow) is examined. Whether it’s examined in hardware or software, it’s still examined. Which means that a firewall will almost ALWAYS be the slowest part of your network. Think of any network interface speed you can: 1G, 10G, 25, 40, 50, 100, etc. Those interfaces on switches and routers are expensive, but they cost nearly nothing in comparison to the firewall that can pass traffic at that given speed! Sure, your firewall may have two 10G interface on it: one in and one out. But can it actually process 10G worth of traffic? Very likely: no. It can’t. Not unless you’ve spent a considerable amount of money on it. Never mind firewalls that can actually process 25G, 40G, or more!

But what do we do instead? How about those aforementioned routers? Do your data centers and offices have some decent routers at the edge? Ones that can process traffic at line rate with an access control list applied to the interfaces? If the answer is yes, then how about moving your security posture there? Remove that extra hop from the network, which will then make your network significantly more reliable!

I have an even better idea: most modern-day OSs have the ability to filter network traffic. And the cool thing about servers is: they scale infinitely. Way easier than network devices do, and definitely easier than a firewall can. Further, they’re infinitely cheaper than either. Put a network security umbrella on your routers; one that lets most things through but blocks certain things that you never want in your network anywhere. Then on each server, allow only the traffic for the services on that server, and block everything else.

What these ideas will ultimately do is provide you with a far more reliable network, and one that’s a lot easier to scale and troubleshoot when something breaks.